I was born in Ireland in the eighties, raised in a catholic household, and educated in catholic schools. I was taught that pride was a sin – one of the seven deadly sins, in fact.

It was painted as arrogance, as vanity. Something to be ashamed of. And shame? Shame was a virtue.

To be clear, I’m not even talking queer pride…we’ll get to that. I’m just talking about regular, good old pride in one’s own self.

In Ireland, we were taught to reject compliments and diminish our accomplishments so as not to seem too proud. If you ever compliment an Irish person on their outfit, they’ll immediately tell you how cheap it was, or how old it is, and that they look like shit.

We also judged people for being proud: growing up, discussions about someone else’s success were usually coupled with phrases like “he’s gotten too big for his boots” or “Miss high and mighty in the big city.”

So, before I was even sure I was gay, I was already afraid of being proud of anything. To baby gay Alan, the thought of being proud to be queer was impossible. Why would anyone be proud of that?

So, I learned to hide. I stayed quiet. I didn’t make friends often, and if I did, I didn’t let them get too close. I hid the way I wanted to express myself, the way I wanted to live.

I was taught, in subtle and not-so-subtle ways, that my existence could make others uncomfortable. And so, I would shrink myself to make others feel safe.

Pride is hard.

I eventually came out, of course; you can only hide for so long before something has to give. When I was 16, I told my parents and a select few friends that I was gay — and was met with just the right amount of fake surprise.

But if I am being honest with you, dear audience, I only really half came out.

When I went to college, and when I got a job, I never talked about my boyfriend openly, or said the name of the bars I drank at on the weekend.

Never talked about the hot guys on TV… but never talked about the hot girls, either. Never lying, but never really being fully truthful.

Even though people probably already knew, I still hid.

The first time I went to a Pride parade, I was about 16 or 17. I didn’t tell anyone – I just showed up, alone, pulled there by a quiet curiosity I couldn’t ignore. I didn’t wear anything rainbow. I didn’t carry a flag. I stood at the edge of the crowd, heart pounding, scanning every face, terrified that someone I knew would spot me. That someone would recognize me and know… The irony of being ashamed to be seen at a celebration of pride isn’t lost on me.

Pride is hard.

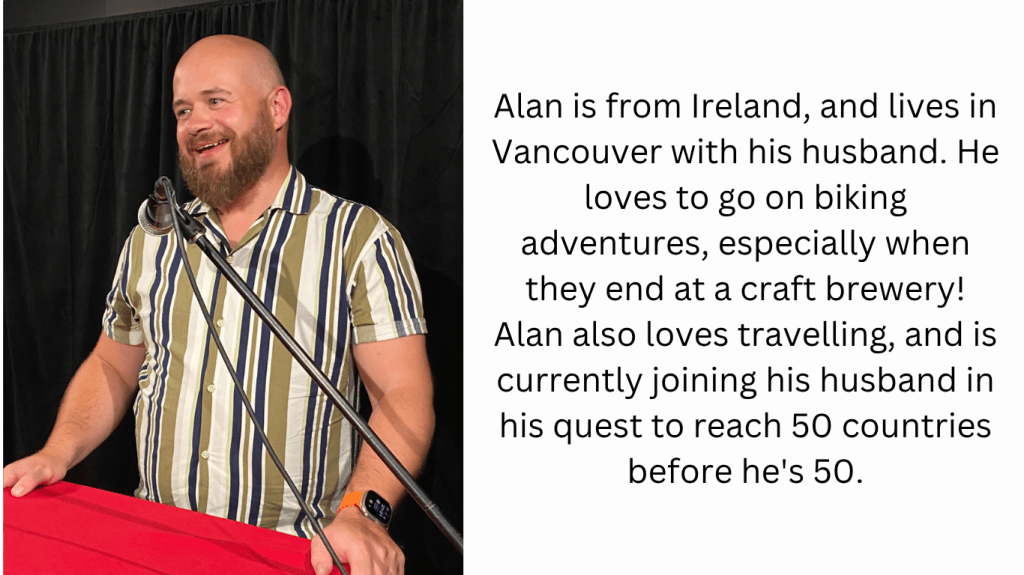

That moment at the parade stayed with me, even as life moved on. I immigrated to Vancouver about eight years ago. I came with my then-boyfriend. Here, we discovered an amazing queer community — something we’d never really had, back in Ireland. My then-boyfriend has since become my now–husband. We’ve made some of the closest friends we’ve ever had.

A couple of years ago, I joined the board of directors and became chair of the board of Vancouver Pride.

If I thought pride was hard before, I don’t think I was prepared for how hard Capital P pride is when you are at the helm of a struggling, underfunded not-for-profit organization, operating in a world with an ongoing genocide, during a time when trans and queer people are under attack globally.

For some people, Pride is impossible.

I had the privilege of being part of the Society and chairing the board through Canada Pride: Vancouver’s biggest pride celebration to date. A truly rewarding, exhausting experience that damn well nearly broke me. We had a record-breaking turnout, our largest parade ever, amazing performances… and threats of violence, budget cuts, and protests.

Friends, I know I’ve mentioned a couple of times now, but:

Pride. Is. Hard.

When I was a kid, and well into my twenties, the idea of wearing nail varnish, or anything even slightly effeminate, was unthinkable. Femininity was something to be feared or hidden.I would worry that I was walking or sitting too “girly” (whatever that means) , I would worry that I wasn’t talking like a “normal” man. All these small things that would consume my brain in an effort to suppress my difference.

But here I am, nearing my 40th birthday and A couple of weeks ago, I debuted as Lady Anal in my first-ever drag performance. I wore a corset, tutu, and 5-inch heels, and danced to Lady Gaga on a stage in front of around 600 people… and let me tell you – DRAG is hard!

I think baby gay Alan would be shocked to see me in a corset and heels—but I also think he’d be proud. Finally.

I often think back to that first parade. Hiding amongst the other spectators, heart racing. I was scared, but there was something else creeping in; something almost indescribable — queer joy. Queer joy isn’t always loud, or even obvious. Sometimes, it’s just the peace of being fully yourself, without apology. I didn’t know it then, but standing at the edge of that parade was the first step toward the centre of it.

Pride is hard… But it’s worth it.

Because every time someone steps up and says who they truly are, the world becomes a better, more interesting place.