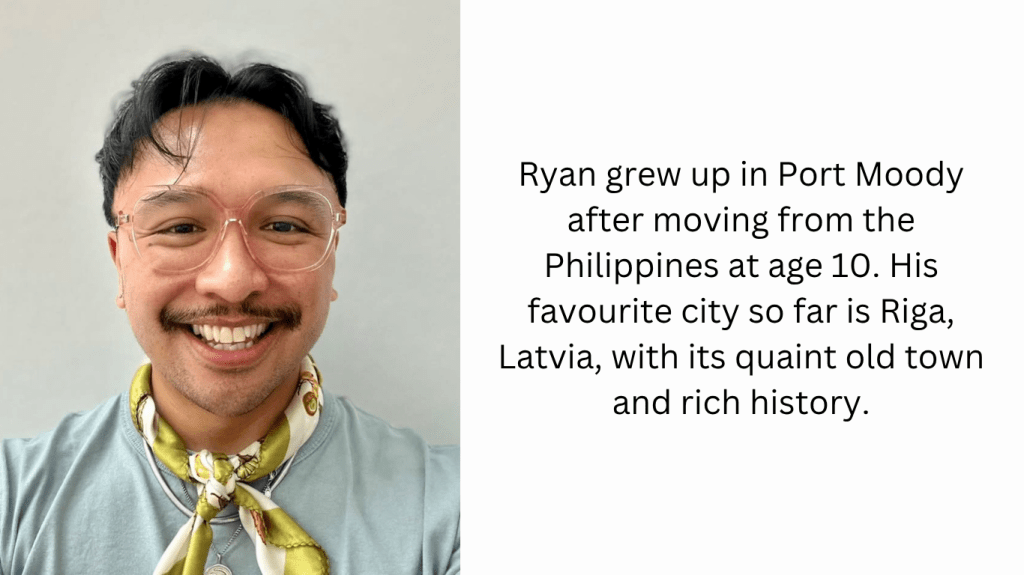

I grew up Filipino.

Which meant I also grew up Catholic, respectful, and quiet when it mattered.

You didn’t talk back. You didn’t question your elders. You didn’t come home too late. And you definitely didn’t talk about queerness.

In our community, you could suspect. You could joke. But no one ever said it.

Being gay was either a punchline or a shameful rumor that hovered around someone until it stuck. So I learned early: keep it tucked away. Smile. Be helpful. Be successful. And I was. Success became my armour. Good grades. Good manners. A carefully curated version of myself.

If I couldn’t belong by being me, maybe I could belong by being perfect.

It wasn’t that I didn’t know I was queer. I did.

I felt it in the way I watched certain people longer than I should—especially my sister’s guy friends. These boys were always around: loud, confident in that casual way boys are when they’ve never had to question their belonging.

They’d play basketball, all shoulders and jokes and zero personal space.

And there I was, always on the sidelines wondering what it would feel like not having to hide.

I wasn’t just crushing—I was studying.

How they existed around each other without fear. They were soft with each other in ways no one called soft. Their masculinity was never questioned. Mine was something I monitored constantly.

And I’d sit there wondering, Do I want to kiss them? Be them? Or just be allowed

near that kind of ease? Let’s be real—probably all of the above.

That’s why my first Pride felt… surreal. It was in Vancouver. I had just started letting myself live more openly—not just online or in whispers, but out loud. I didn’t know what to expect.

I just remember putting on this yellow polo shirt—something bright, safe, cheerful. I added a rainbow pin, maybe some beads I’d been handed by a volunteer. It felt like putting on armour, but softer. Like permission. I watched from the sidewalk as the parade moved past. Rainbow flags everywhere. Glitter. Music. People cheering and kissing and dancing in the street like the whole city had finally taken a deep breath.

And then I saw it—the TD float, blasting music with half-naked people dancing in the sun. Glistening bodies. Queer joy. Sweat and pride and freedom.

But here’s the thing: I didn’t feel like I was part of it. I felt like a spectator. Like I was watching someone else’s celebration, not mine.

I was smiling, clapping, even laughing—but I was still on the curb. Still unsure. Still asking myself, “Am I queer enough to belong here?”

It wasn’t shame exactly. It was distance. Like I had stepped into the world of Pride, but I hadn’t quite arrived in myself yet.

It took me a few more years, and a move across the ocean, before I’d feel anything different. Brussels Pride caught me off guard. I hadn’t even planned to go, but I found myself in the middle of the city, swept up in the energy.

This wasn’t a hyper-produced parade with big floats and barricades. It felt open. Messy. Intimate.

People weren’t just watching—they were walking. The barriers were barely there. Anyone could step off the sidewalk and join the procession. And people did. People of different backgrounds, mingling, dancing and exuberantly celebrating.

Young people marching with their chosen family. Straight friends carrying signs that said, “I’m here because I love someone queer.”

And the soundtrack? Pure Eurovision chaos. From someone blasting “Tattoo” by Loreen like it was church, to a rhythmic chant to “Europapa,” it was enchanting.

Every corner had its own beat. Every queer had a flag. Every moment felt like home—if your home also occasionally served techno with a side of identity crisis.

Honestly, if you’re a Eurovision fan, hit me up, we clearly speak the same emotional language: high drama, bold fashion choices, and the occasional key change that saves lives and after some time I stepped off the sidewalk.

For the first time, I didn’t feel like I had to earn my place.

I wasn’t perfect. I wasn’t loud. I was just present. And that was enough.

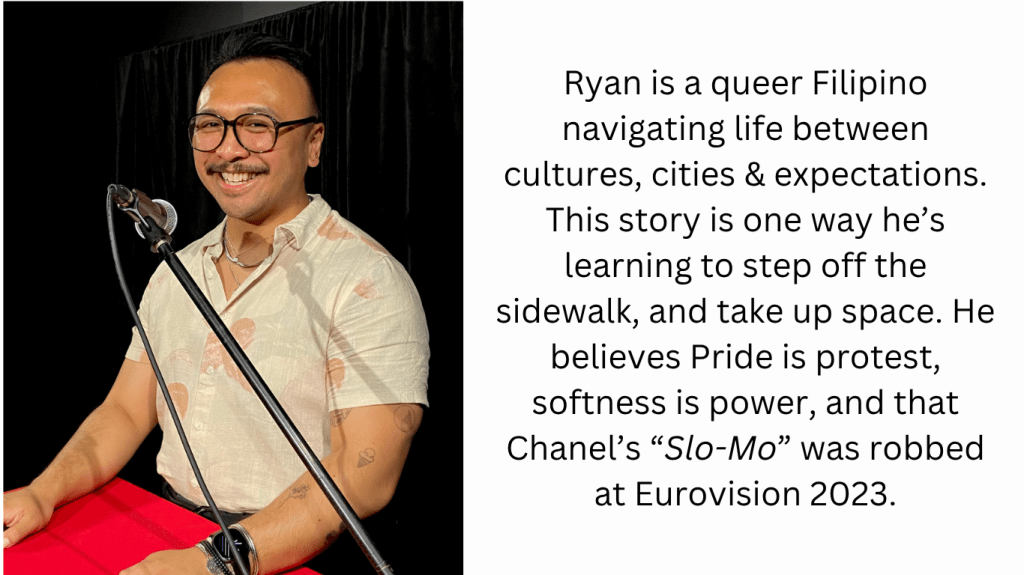

When I think about Pride now, I don’t think about the floats or the glitter or the corporations with their rebranded logos. I think about that moment in Brussels—stepping off the sidewalk and into the street.

Because Pride isn’t a performance. It’s a process. It’s the slow unlearning of shame. It’s the decision to stop apologizing. It’s choosing joy even when the world has only taught you fear.

And yet even now, when I walk into certain spaces—queer or not—I still carry that quiet calculation: “Am I too much here? Or not enough?”

Because queerness is not a monolith and the mainstream image of Pride still doesn’t always look like me.

There’s a kind of queerness that gets celebrated more easily.

Usually white. Usually cis. Often male. Lean. Loud.

Unapologetic in a way that feels less like protest and more like branding.

And sometimes, in those clubs, those professional events, those “inclusive” queer spaces, I still feel like I’m back on the sidewalk. Watching the parade.

I’ve been the only brown face in a meeting. I’ve had coworkers pull me aside to tell me I’m “so well-spoken,” as if it’s a surprise. I’ve had white queer people talk over me in meetings about diversity.

I’ve been fetishized for my brownness. Othered, even in intimacy.

And I’ve seen how people treat me differently when I show up femme—when I wear non-conforming garments, when my voice softens, when my wrists move too freely. Sometimes, being a queer person of colour means walking into rooms that claim to celebrate you, but only if you come in fragments.

Only if you leave the messiness, the accent, the ancestors, the softness, the trauma, and the realness at the door.

But that’s not who I am anymore. I don’t fragment myself for anyone now.

Because Pride isn’t just about who you love. It’s about how you insist on your wholeness in a world that keeps trying to carve you into pieces.

I once heard someone say:

“We don’t just want to be tolerated—we want to be accepted.” And that hit me.

Because for so long, I’d been satisfied with tolerance.

With not being bullied. With not being the punchline. With being allowed to exist.

But now? I want more. I want room to be joyful. To be complicated. To be brilliant and brown and queer and soft and taken seriously.

I want acceptance. Not as a concession, but as a given.

I’ve found power in taking up space—not always loudly, but fully. In speaking up at work when something feels off, even if I’m the only one who notices. In mentoring other queer folks of colour, so they don’t have to wait as long as I did to feel seen. In holding space for softness, for mess, for nuance.

In telling my story, especially the parts that aren’t tidy.

Because this is Pride, too. Not just rainbow floats and party weekends, but healing. Boundaries. Audacity. The choice to keep showing up, again and again, in rooms that weren’t designed for you, and remaking them in your image.

Now, when I think about my journey, from hiding behind grades in a Filipino household, to staring longingly at sweaty basketball boys, to watching the parade in Vancouver, to marching through a sea of techno and tears in Brussels—I realize I was never chasing a performance.

I was building a relationship with myself. One where I could love all of who I am.

Brown. Queer. Soft. Strategic. Sensual.

Not half of anything. Not apologizing anymore.

So if you’ve ever felt like Pride wasn’t made for you—too brown, too quiet, too complicated—I hope you know this:

You don’t have to wait for someone to invite you in. You belong here.

Even if you don’t wear glitter. Even if your pride looks like staying in.

Even if your anthem is Loreen and you cry to “Europapa” once a week.

Because Pride is not a moment.

It’s a practice. A rhythm. A reclamation.

And it’s yours.