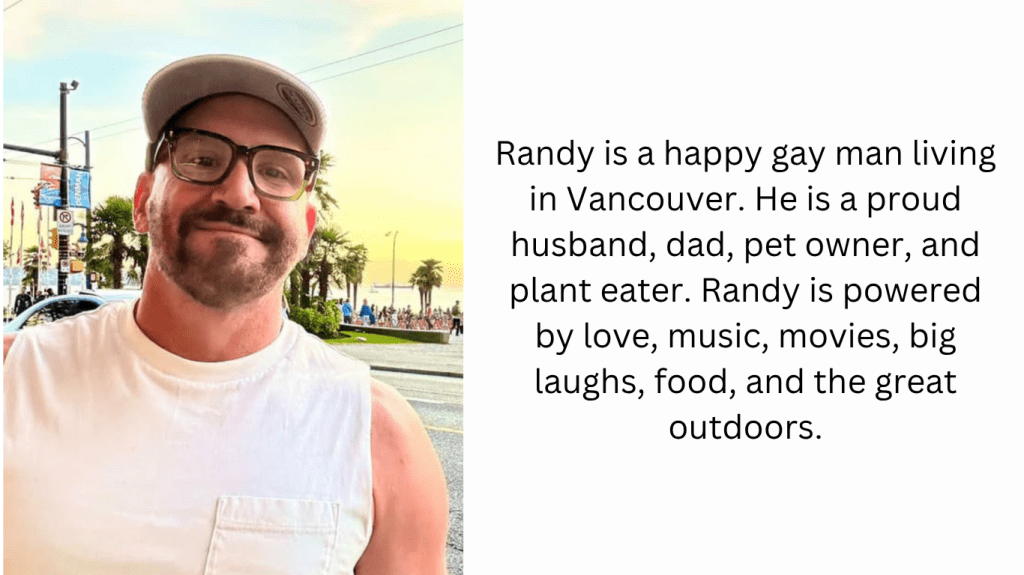

When I came out almost 10 years ago, I could never have anticipated the journey that would lead me to my life partner. Let alone expect to be someone’s husband, for the past 30 days. As I stand here today, I am grateful for every minute of it, even the hard parts. I’m thrilled to say that the most wonderful man, to quote Beyonce, put a ring on it. Technically, we both did… Happy endings aren’t just for bathhouses. I’d like to take a few minutes to tell you about our recent wedding and elopement.

Our relationship, while, of course not perfect, has been relatively smooth when it comes to planning things: since I like doing all general planning things and Parm is extremely detail-orientated. I ride the hot-mess ADHD express and lose my dopamine rush when it comes to the more precise points. It’s truly a great match to have planning a vacation, moving apartments, redecorating, but when planning a wedding it can be a blessing and a curse.

Parm and I got engaged December 2023 and since we’re both planners we wanted to have a long engagement to make sure we had adequate time to plan things out. A quick backstory on how we got engaged. I decided to surprise him on our anniversary, since Parm hates surprises. It was the one way I could ensure he wouldn’t be suspicious I was planning something. I had tried, and failed, to surprise Parm a few times. I thought It would be a good idea to take him to high tea, after he was at the gym in street clothes, and was underfed from a leg day. For the proposal, I tried to keep the destination a secret. But who would have thought he would’ve figured out I was taking him to Circle Wellness on Granville Island of all places. On the walk to where I had arranged his friends to meet us, Parm launched into a diatribe about why I shouldn’t try and surprise him anymore. Mainly since he wanted to know the plan to be mentally prepared and be properly dressed for the occasion. All I could think of in the back of my mind was, oh boy, you’re in for one major surprise in 5 minutes…

Going back to wedding planning, one of the greatest strengths I’ve learned since coming out is that there isn’t a “right” or “normal” way to be queer. So many social norms and expectations are shed when we come out and start living as our queer, authentic selves; especially when you enter a relationship. In gay relationships, nothing is assumed. You must clearly and openly communicate your roles, your responsibilities, and expectations. When Parm and I moved in together, we had to discuss how laundry, cooking, cleaning worked.

When we were planning our formal wedding, we had to figure out how walking down the aisle would work. If we wanted to include gendered cultural wedding traditions, how that would work. Being able to define all these things on our terms was (and is) a powerful thing, and I hope the same intentionality and partnership starts to show up more in hetero relationships. Be open and communicate what works for you as an individual and as a couple, and don’t just assume your role based on gender. We initially had a the “big white wedding” planned. Well, maybe not big, since we had capped it at 80 people. And maybe not all that white, since Parm has a big Indian family.

We were excited for our formal wedding here in Vancouver and placed the deposit for our dream venue, but as the time started coming closer to actually need to put pen to paper, we just weren’t excited at the idea. It just seemed like work and didn’t really feel like us. We toyed with the idea of eloping, at first here in BC, by doing a helicopter wedding to ensure none of our family could sneak in. But we had already planned on doing a honeymoon… before our wedding I may add, in the Faroe Islands and Mallorca. Why were we going to the Faroe Islands? Parm had seen it and wanted to explore it for it’s beauty. I wanted to go because there was a sweater shop I wanted to go to. Parm had an excellent idea to have our elopement in the Faroe Islands since the nature is beautiful and dramatic.

We cancelled our Vancouver wedding and instead carried out our plan to do our wedding there. And it was the best decision that we could’ve made. But first we had to make it legal and literally got married in slippers and bathrobes here in the West End. We forgot to give our officiant a heads-up, so she was a little surprised. It was unapologetically us. We love to travel, we love going to random places, we love hiking and nature, and we love doing things differently. We spent the whole day exploring the country with a local photographer, who proclaimed that five tourists at a site was “busy”. We think he would have an aneurysm seeing the steam clock crowds in summer…

We did everything that we loved. We explored a small picturesque town with colourful houses. Went to a waterfall and scaled the rocks in dress shoes. Did our vows in the rain. Got, possibly a top-10 burger, at a gas station. And ended the day doing a hike in our tuxes to see one of the most beautiful parts of the Faroe Islands, Traepania, Where there is a lake above the ocean, backdropped by sheer cliffs. We were tired, muddy, and had our wedding night back at the hotel, lying in bed with pizza. In short, we wouldn’t have done things any different, and it was a perfect wedding day.

I’m just so happy that Parm is the person I got to marry. The full story of how we came together is a story for a different day, but I initially tried to push him away. I had come out of quite a toxic relationship and wasn’t ready to date. He actually went on a few dates with my ex and pieced it together by the missing furniture in our respective apartments. Needless to say, he learned that I wasn’t the crazy ex.

In spite of all of the emotional push and pull (and the occasional self sabotage, of course) Parm stuck by my side. He gave me endless patience, a safe space to be irrational if I was spiralling while trying to process my trauma, and showed me that not everyone is out to get me. That I could feel safe enough to trust someone again.

I’m looking forward to building a life together and this next chapter is just the beginning. I’m just excited to be writing this one together as husband and husband.