Growing up gay in a small town is like learning to whisper when all you want to do is sing. You get really good at editing yourself; at shrinking. I grew up in a town of 5,000 people, where most people knew each other, or at least thought they did. You learn quickly how to blend in, when the cost of standing out is being left out entirely. And so, I did what a lot of queer kids do: I said I wasn’t. I hid.

I knew I was different early on, but I didn’t have the language for it, or the confidence to claim it. In a place like that, being gay wasn’t something you admitted. It was something you denied, or joked about, before anyone else could weaponize it. I learned how to pass. How to act. How to keep one part of myself tucked away so well that sometimes even I forgot where I put it.

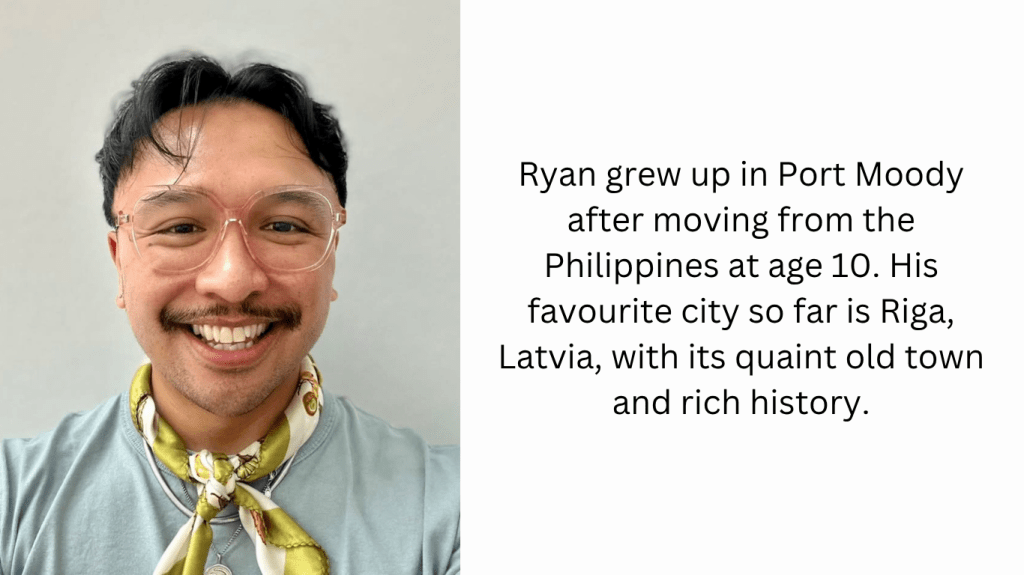

Then I met someone who had hidden just as well as I had. Someone from an even smaller town—500 people, if you can believe it! I used to joke that if I had it bad, he had it worse. But the truth is, we had something in common: we both grew up thinking we had to be less to be loved.

At first, being together was like finding a mirror. Not just in the obvious way—both of us boys, both of us figuring it out—but in how deeply we understood the effort it took to make ourselves palatable to the world. We didn’t just fall in love; we fell into safety. Into understanding. Into survival.

But we also fell into habits that mirrored our upbringing. We stayed quiet. We didn’t talk about our relationship in certain spaces. And even though our families knew we were gay, and knew we were together, we kept things toned down. We didn’t call each other “boyfriend” around them. We didn’t show affection. To them, I think we were just… neutral. Not hiding, exactly, but not fully seen either. We weren’t straight, but somehow, we still managed to look it.

For a long time, we didn’t feel like Pride was for us. It felt like something other people did: louder people, braver people. People who had figured it out. People with less to lose. It wasn’t shame, exactly. It was just… caution.

Then in 2019, we finally went to our first Pride event. Not in Canada. Not even in North America. It was in Manchester, England. And to be honest, one of the biggest reasons we went was because Ariana Grande was headlining the closing show. We had already seen her in April that same year… but Ariana at Pride? That felt like something different. It felt iconic. It felt like a good enough excuse to finally show up.

We booked the trip half for her, and half, I think, for ourselves, though we wouldn’t have admitted that then.

I remember walking down the street and hearing the music before we even saw the crowd. There were rainbow flags everywhere. Drag queens, couples holding hands, kids in rainbow tutus, protestors with signs, allies cheering. It was colourful and chaotic, and so beautifully alive. It was everything we weren’t used to. Everything we had quietly denied ourselves.

And for the first time, we didn’t feel like we were borrowing space. We felt seen. Not just tolerated. Not just allowed. Seen.

It was overwhelming, in the best way. We danced. We laughed. We kissed, even. Right there in the street, surrounded by strangers who clapped and cheered, and kept on dancing. I had never felt more free; or more aware of just how tightly I’d been holding myself.

That was the year Pride stopped being a word and became a feeling.

Since then, we’ve been to more Pride events, but not dozens. Just a few that mattered. Vancouver Pride has become a bit of a tradition for us. And this year, we went to Winnipeg Pride with the biggest group of gays I think I’ve ever travelled with. It was loud, joyful, chaotic, in the best way. A complete contrast to how we first learned to be gay: quietly, cautiously, carefully.

Every time, we let go a little more. Not just in public, but with ourselves. We let ourselves be soft. We let ourselves be loud. We remind ourselves that we don’t have to earn our space. We just get to be.

And here’s the thing: it’s not always perfect. Sometimes Pride is corporate. Sometimes it’s messy. Sometimes, it doesn’t represent everyone the way it should. But at its core, when you strip away the noise and the politics, Pride is about the right to exist fully. Without apology. Without compromise.

It’s a reminder that joy is resistance. That celebration is healing. That there is room for every kind of queer story, even the quiet ones. Even the ones like mine.

Because the truth is, I don’t have a dramatic coming out story. I didn’t run away. I didn’t get kicked out. I didn’t have to fight tooth and nail for acceptance. But I did fight. Quietly. Internally. For years, I fought for the right to be honest about who I am. I fought to believe that I didn’t have to shrink to be loved.

And that’s what Pride gave me. It gave me back the parts of myself I thought I had to hide. It showed me that visibility isn’t just about being seen by others. It’s about being seen by yourself.

So now, twelve years later, I get to stand next to the same man I met when we were both still scared. We’ve grown together. We’ve healed together. We’ve learned that the world is big enough for love like ours, and that we don’t have to water it down.

We still hold hands in some places, and not others. We still measure our surroundings before we kiss in public. The world isn’t perfect. But we are no longer pretending we’re something we’re not. And that matters.

Pride, to me, means hope.

Hope that someone else growing up in a small town—someone who’s hiding, someone who’s scared—can see people like us and feel just a little less alone.

Hope that the next generation won’t have to learn how to whisper.

Hope that one day, we won’t just be accepted—we’ll be celebrated.

Not because we’re exceptional, or brave, or resilient. But because we’re here.

And that’s enough.